DPG Policy Note

India and the US: A Growing Engagement

US President Donald Trump received a rousing reception at the ‘Namaste Trump’ event in India on February 24, 2020. This marked a continuum to the warm reception that Prime Minister Narendra Modi had received at the ‘Howdy Modi’ event in September 2019 in Houston, Texas. In spite of coming from very different backgrounds, over the past few years, President Trump and Prime Minister Modi seem to have developed a certain camaraderie and mutual respect which was in full display during the visit. Behind the bonhomie that marked the occasion, the Trump visit also showcased the people-centric nature of India-US ties: two democratic societies engaging with each other and standing together.

A Multidimensional Relationship

It is frequently argued that the uptick in India-US relations is a consequence of the rise of an assertive China. Analysts took note that President Trump indirectly brought out the stark contrast between India and China in his speech when he remarked, “there is all the difference in the world between a nation that seeks power through coercion, intimidation, and aggression, and a nation that rises by setting its people free and unleashing them to chase their dreams.”[1] Indeed, there is a strong segment of opinion that suggests that the reorientation of the United States’ strategic approach from the Asia-Pacific to the Indo-Pacific is an attempt by Washington to develop convergences with New Delhi to balance China in the region.

However, to define the scale of the India-US bilateral relationship merely through the Chinese lens would not be accurate. These relations are multidimensional and have been growing rapidly for the past two decades. Further, the relationship is enjoined by the presence of over 4 million Indians[2] in the United States, a community which has been contributing extensively to the people-to-people interactions between the two nations. The widespread use of the English language in India has facilitated communication between the two countries. As liberal democracies, their societies have an intuitive understanding of the political constraints and opportunities under which the leadership in both countries works.

Some among India’s opposition have dismissed President Trump’s visit as a spectacle lacking in substance, but the compulsive anti-Americanism among sections of Indian opinion with its usual caution against developing a close relationship with the United States was largely absent this time around. However, segments of civil society tried to draw the United States into India’s domestic debates in the Citizenship Amendment Act and the perceived rise of nationalism. They were disappointed when President Trump refused to moralise, saying, “I don’t want to discuss that. I want to leave that to India, and hopefully they’re going to make the right decision for the people. That’s really up to India.”[3]

Trade: Dealing with Deficits and Discussing Next Steps

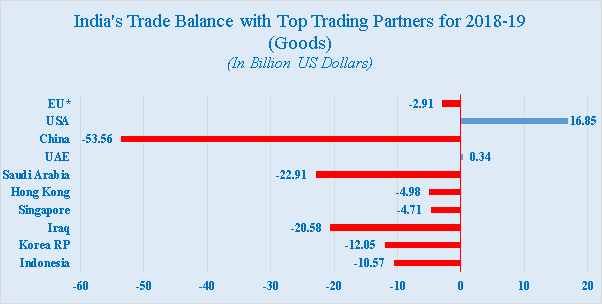

Trade is incrementally becoming an important factor in bilateral relations for number of reasons. Partly, the eagerness to move closer to the United States seems to be stemming from the recognition of the economic importance of Washington to New Delhi. The United States is India’s single largest trade partner with the total bilateral trade in goods and services amounting to USD 142.6 billion in 2018.[4] India has a trade deficit in goods with 8 of its top 10 trading partners, with the exception of the United States and the UAE (see Graph below). It is important that New Delhi continues to therefore scale up its trade relations with Washington. Both countries have been conducting intense negotiations to finalize a limited trade agreement and comments by leaders during the visit gave an impression that some progress has been made. For instance, PM Modi stated that “President Trump and I have agreed today that the understanding that has been reached between our Commerce Ministers, let our teams make it legal. We have also agreed to start negotiations for a bigger trade deal.”[5]

*Trade balance with EU does not include trade with United Kingdom.

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. Graphics: DPG

The continuing delay in the conclusion of a trade deal between India and the United States can be attributed to many factors. While Trump comes from New York, his political base is in rural America and not in industrialized segments or population centres located on the Eastern and the Western coasts of the United States. As a consequence, President Trump is interested in significant concessions from trading partners in the agricultural sector. This was also evident in the Phase 1 trade deal signed between the US and China in January 2020.

Nonetheless, it appears that the Indian negotiating team is open to balanced trade-offs. For instance, during President Trump’s visit, it was noted by senior Indian government officials that concessions to the US on dairy could result in significant gains in others sectors.[6] The other contributory factor for the delay in the trade deal is the divergence between the two sides in perceptions of India’s economy. The United States is treating India as a developed economy. In contrast, India rightly sees itself as a developing economy despite its GDP of USD 2.7 trillion (as of 2018).[7]

In spite of the fact that the United States is a preponderant power, President Trump’s negotiation style and his tendency to frame trade outcomes as “spectacular” victories for the US and a “colossal” loss for other countries is a source of concern. In addition, there is a large constituency within the United States which is worried about the relative decline of Washington’s global role and influence. In order to address such emotional requirements within US society, President Trump has deployed the slogan of ‘Make America Great Again’. President Trump’s domestic compulsions and the need for communicating that he is ‘winning deals’ on behalf of the United States adds complexities to trade negotiations, as does his tendency to define ‘winning’ as securing a reduction in trade deficits. For instance, in 2018 the US trade deficit with India (USD 20.8 billion) was minuscule compared to the trade deficit with China (USD 378.6 billion).[8] However, President Trump has often placed India and China under the same bracket by referring to them as protectionist economies. During the press conference in Delhi, President Trump complained that India is charging very high tariffs and like Beijing, New Delhi will have to reduce its tariffs to have a trade deal.[9] Nonetheless, if India’s growing energy imports, defence procurements and purchases of civilian aircraft from the US are taken into account, this trade deficit comes down very substantially.

Given concerns about excessive dependence on Chinese supply chains, India can also emerge as an attractive alternative investment destination. Of course, India will need to improve further on the Ease of Doing Business and scale up its Logistics Performance Index (LPI).[10] Such improvements will enhance the competitiveness of Indian industry and provide space for changes in regulatory tariff structures, enabling India to take better advantage of the existing geo-economic opportunities.

Defence: Trust and Technology

While trade negotiations are yet to demonstrate significant progress, there is growing comfort and trust between Washington and New Delhi in the realm of defence cooperation. This has prompted the United States to offer advanced weapons systems to India. New Delhi has already procured systems such as P-8I anti-submarine warfare aircraft, C-17 Globemaster strategic lift aircraft, Apache attack helicopters, C-130J Super Hercules tactical transport aircraft, Chinook heavy-lift Helicopters, AN-TPQ weapon locating radars, and M-777 ultra-light howitzers from the United States.[11] During President Trump’s visit, further sales of MH-60R naval helicopters and AH-64E Apache helicopters to India were announced.[12] Discussions are ongoing on the provisions of Integrated Air Defense Weapon System (IADWS) and Sea Guardian armed UAVs to India.[13] Given the growing presence of China in the Indian Ocean Region, India-US defence cooperation needs to prioritize ISR, MDA and ASW capabilities. While the US has a preference for FMS sales, efforts should be made to ensure that US defence industry also participates in India’s defence RFP. In spite of increased purchases from the United States, Russia still accounts for almost 60% of India’s defence equipment. India needs to ensure at least some components of these legacy defence platforms are manufactured domestically in the coming years.

Moreover, there is growing recognition in India that future military confrontations will be short and technology-intensive. In order to respond to these new challenges, high-tech defence transfers and technology cooperation with the US assumes even greater importance for India.

Connecting the Dots: Energy and Infrastructure

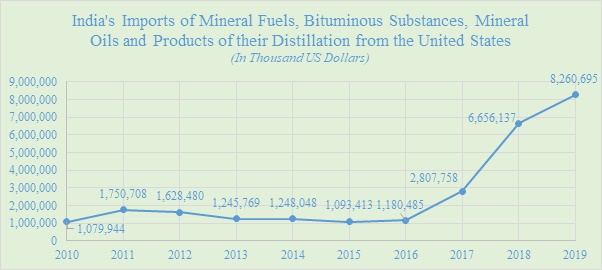

The Joint Statement issued following the Modi-Trump summit refers to strengthening of the Strategic Energy Partnership between the two countries. During the visit, a Letter of Cooperation between Indian Oil Cooperation Limited and the ExxonMobil India LNG Limited was exchanged,[14] which is expected to ease the delivery of natural gas through containers to cities in India which lie outside the pipeline network.[15] The graph below illustrates the sharp increase in India’s energy imports from the US, which have led to a diversification of its energy sources beyond the Gulf.

Source: International Trade Centre. Graphics: DPG

In the recent past, China’s aggressive pursuit of BRI infrastructure projects have increased risks of debt traps and impaired sovereignty. In order to address such challenges, the India-US Joint Statement issued during the visit stated that “Prime Minister Modi and President Trump expressed interest in the concept of the Blue Dot Network…to promote high-quality, trusted standards for global infrastructure development.” The Blue Dot network, which is an initiative of the G7 and Australia,[16] certifies both physical and digital infrastructure projects on various parameters such as quality, transparency, financial viability and security.

Afghan Anxiety

The Joint Statement issued following the Trump visit states that both countries have a shared “interest in a united, sovereign, democratic, inclusive, stable and prosperous Afghanistan”.[17] While the US desire to withdraw from Afghanistan is understandable, the impact of the US-Taliban agreement which appears to legitimize the Taliban as a credible political actor with valid demands is a source of concern for India and the Afghan government alike.

India’s approach towards an Afghan-owned and Afghan-led peace process is premised on strengthening the capacity of the Afghan state and its military. In order to achieve this objective without deploying troops on the ground, India will need to enhance support for military training, counter-terrorism, intelligence grids and infrastructure building. It must also maintain progress in developing the Chabahar Port, which provides a vital alternative access route to Afghanistan.

Building Indo-Pacific Convergences

The Joint Statement hints at a four-pronged strategy to build on India-US convergences in the Indo-Pacific: (1) enhancing bilateral consultations (such as the 2+2 Ministerial mechanism); (2) strengthening trilateral dialogues as well as the Quadrilateral framework; (3) ensuring “sustainable and quality infrastructure development in the region”; and (4) pursuing “partnership between USAID and India’s Development Partnership Administration for cooperation in third countries”.[18]

Much work clearly lies ahead to build further on what can become a defining partnership for the 21st century. But there can be little doubt that for the moment, both nations can celebrate the results of what President Trump defined as “diplomacy of great friendship and respect”.[19]

[1]“Remarks by President Trump at a Namaste Trump Rally”, White House, February 24, 2020, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-namaste-trump-rally/

[2]“Population of Overseas Indians (Compiled in December, 2018)”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, available at https://mea.gov.in/images/attach/NRIs-and-PIOs_1.pdf

[3]“Remarks by President Trump in Press Conference,” White House, February 25, 2020, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-press-conference-4/

[4]“U.S.-India Bilateral Trade and Investment”, The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), August 15, 2019, available at https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/south-central-asia/india

[5]“Translation of Press statement by the Prime Minister on the State Visit of the President of the United States of America to India,” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 25, 2020, available at https://mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/32420/Translation_of_Press_statement_by_the_Prime_Minister_on_the_State_Visit_of_the_President_of_the_United_States_of_America_to_India

[6]Priscilla Jebaraj, “Small concession to U.S. on dairy, can yield gains in other areas: official,” The Hindu, February 25, 2020, available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/small-concession-to-us-on-dairy-can-yield-gains-in-other-areas-official/article30916518.ece

[7]“Gross Domestic Product 2018”, World Bank, December 23, 2019, available at https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf

[8]“The People's Republic of China,” The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), available at https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/china-mongolia-taiwan/peoples-republic-china

[9]See “Remarks by President Trump in Press Conference,” White House, February 25, 2020, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-press-conference-4/

[10] The LPI is an interactive benchmarking tool created to help countries identify the challenges and opportunities they face in their performance on trade logistics and what they can do to improve their performance. See World Bank, available at https://lpi.worldbank.org/

[11]Snehesh Alex Philip, “INS Arihant, Chinook, P-8I — Game-changing Indian Military Inductions in the Last Decade”, The Print, December 29, 2019, available at https://theprint.in/defence/ins-arihant-chinook-p-8i-game-changing-indian-military-inductions-in-the-last-decade/342022/

[12]“Joint Statement: Vision and Principles for India-U.S. Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 25, 2020, available at https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32421/Joint_Statement_Vision_and_Principles_for_IndiaUS_Comprehensive_Global_Strategic_Partnership

[13] See Sebastein Roblin, “More U.S.-India Arms Sales Could Follow $3.5 Billion Helicopter Deal”, Forbes, February 26, 2020, available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/sebastienroblin/2020/02/26/modi-and-trump-sign-35-billion-helicopter-deal-more-could-follow/#4161d52523aa;

Also see “US approves sale of armed drones, offers missile defense systems to India”, The Economic Times, June 8, 2019, available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/us-approves-sale-of-armed-drones-offers-missile-defense-systems-to-india/articleshow/69701845.cms?from=mdr

[14]“Documents concluded during the State Visit of President Donald J. Trump of the USA”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 25, 2020, available at https://www.mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32419/Documents_concluded_during_the_State_Visit_of_President_Donald_J_Trump_of_the_USA

[15] “ExxonMobil, IOC ink gas transport pact”, Economic Times, February 25, 2020, available at https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/oil-gas/exxonmobil-ioc-ink-gas-transport-pact/articleshow/74292986.cms

[16]“Transcript of Special Media Briefing by Foreign Secretary (February 25, 2020),” Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 26, 2020, https://mea.gov.in/media-briefings.htm?dtl/32429/Transcript_of_Special_Media_Briefing_by_Foreign_Secretary_February_25_2020

[17]“Joint Statement: Vision and Principles for India-U.S. Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 25, 2020, available at https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32421/Joint_Statement_Vision_and_Principles_for_IndiaUS_Comprehensive_Global_Strategic_Partnership

[18]“Joint Statement: Vision and Principles for India-U.S. Comprehensive Global Strategic Partnership”, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, February 25, 2020, available at https://mea.gov.in/bilateral-documents.htm?dtl/32421/Joint_Statement_Vision_and_Principles_for_IndiaUS_Comprehensive_Global_Strategic_Partnership

[19] “Remarks by President Trump in Press Conference”, The White House, February 25, 2020, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-press-conference-4/